Today, as women across the globe continue to passionately fight for their rights and strive for equality, it is more important than ever to take a moment to recognize and honor the remarkable efforts of the women who have fought so hard for so long, paving the way for future generations.

From the 1800s to the 1900s, women’s traditional roles in the household underwent significant changes as society transitioned from a predominantly rural lifestyle to the Industrial Revolution. As we commemorate the end of Women’s History Month, the stories of women throughout the history of Haverstraw and the greater Hudson Valley brick industry must be told. Women have been subject to a second-class status throughout history and into the present by various means, from cultural practices to law.

De Noyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

From 1776 to 1845, women faced significant cultural and legal limitations that restricted their roles both inside and outside the household. The Cult of Domesticity culturally defined women’s value primarily as child-bearers and caretakers, confining them to domestic spheres and limiting their opportunities in the community.

Coverture, a historical legal doctrine, stipulated that upon marriage, a woman became the property of her husband, effectively barring her from significant participation in public life. Under the system of Coverture, women suffered economic disempowerment, often lacking control over their wages and unable to claim their earnings for personal use. Coverture also prohibited women from owning property, making them economically vulnerable, and they were denied bodily autonomy of their own bodies and those of their children (something we are still struggling with today). This also affected unmarried women, who largely had no means to sustain themselves [1].

As a repercussion of these practices, women’s actions, agency, and lives in the historical record are scarce and seldom found. Our objective is to research the instances they are mentioned and shine a light on these previously untold stories.

Working Class Women

Before the second Industrial Revolution of the 1850s that led to the Hudson River brick industry expanding exponentially, women were often sought for jobs that fell in line with the Cult of Domesticity. Newspaper advertisements of employment opportunities present this phenomenon.

These advertisements ran small and in local sections as, more often than not, women were hired amongst private persons in private homes, not by businesses or corporations. For example, one advertisement written by ”Mrs, W. P. Foss” read as follows: “WANTED- Girl to do upstairs work and take care of children.” Another read “Girl or woman wanted for general housework. Wages $12 a per month.” [2]

When it came to employment, Black and Brown women experienced "Triple Oppression" because they faced discrimination based on gender, race, and class. [3]

Advertisements, such as this one published in the Rockland County Times, reinforce the notion that women were expected to do housework, such as cooking and cleaning, to have value. Thus, women were pictured in advertisements for cooking ware. Black and Brown women were never the faces of these advertisements. [5]

They often were segregated and denied opportunities simply because of their skin color. An advertisement in a local newspaper underscores this issue, revealing that Martin A. Driscoll would only hire a "white girl for general housework." [4].

With the Married Women Property Act of 1848, working women, previously confined to their homes, began to work in industrial settings.

Increasingly, there were more instances of women working in manufacturing.

For example, The Fourteenth Annual Report of the Factory Inspector, published in 1900, cited Print Works, the largest employer in Rockland County, employing 155 women over 18 and 24 girls under 16; Home Silk Mills of Haverstraw (the only company that employed more women than men) employing 92 females over 16 and seven under; Richard E. King of Haverstraw employing 14 women; William E. Tuttle of Haverstraw hiring 19 women; Conrad Doersch hiring 16 women; and Shoe manufacturers Eberling Bros, Henry Long & Co., and C. Salome & Co. of New City employing 31 women. [6]

Rockland County Times.

In the case of brick manufacturing, the industry was fully perceived as a man’s job, one that a woman could conceivably have no productive or meaningful place. As evidenced in an advertisement for “Moulders, Dumpers, and Pallet Landers” at the Passaic Brick Company, “BRICKYARD MEN WANTED” was bolded and enlarged. [7]

Despite the various obstacles thrown in front of women, they still labored in the brickyards. While there are no pictures in our archives of women working the brickyards according to our ledgers and to the Rockland County Times, “women ha[d] assisted their husbands in hacking brick when he was anxious to do overtime.” [8]

De Noyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

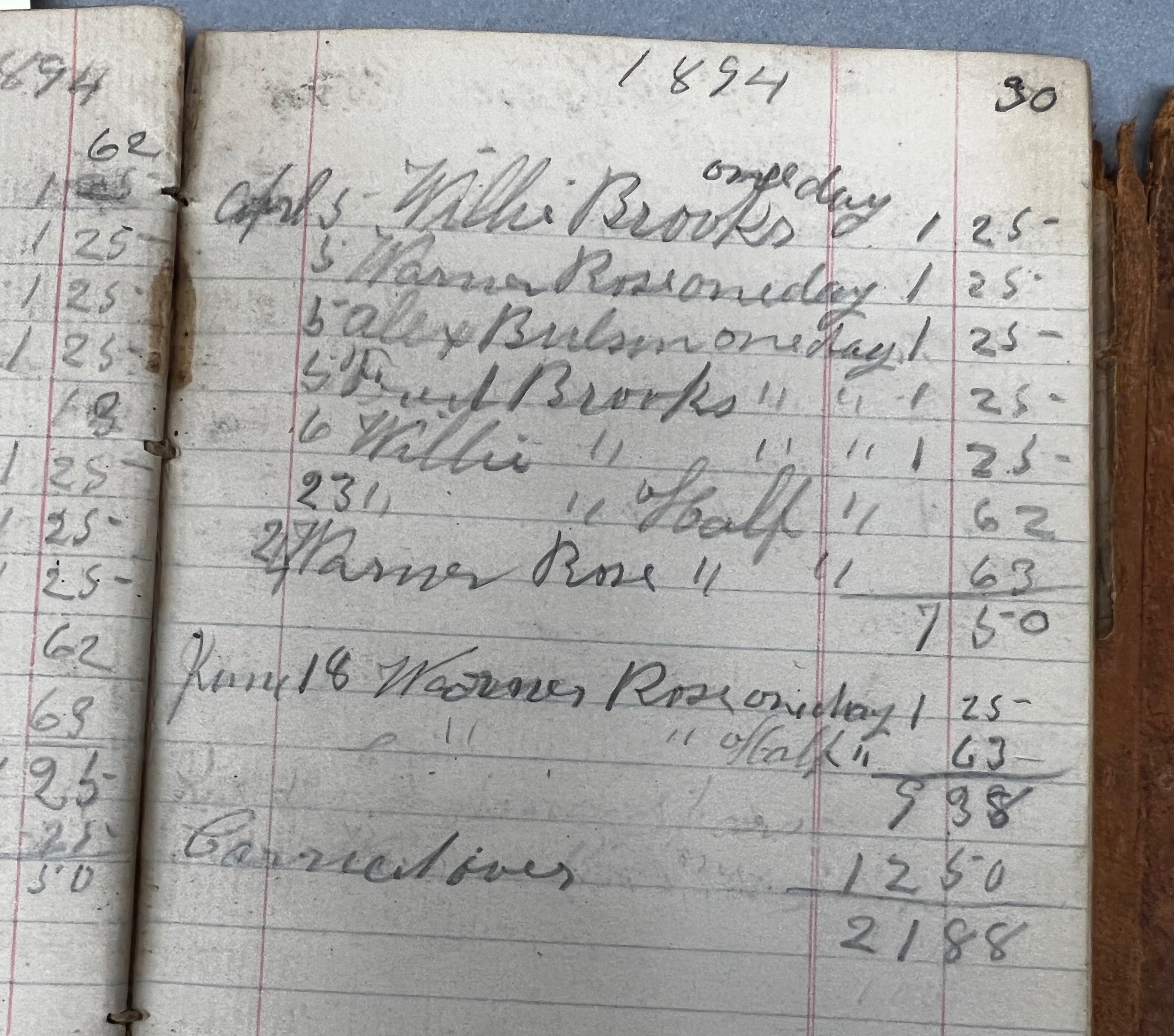

Hacking is the term for stacking green bricks. A complete ”hack” contains 10,000-12,000 bricks and needs to dry for one to three days and nights, depending on the weather. According to our archives, Women earned $2.00 a day, and children earned on average $1.25 a day. [9]

At the turn of the 20th century, a new era of brickmaking unfolded, “for the first time in the history of brickmaking,” a woman was employed “doing a full day work and receiving a man’s pay” on the yard of Mathew Waldron, leased on the Eckerson property.

According to the Times, “a well-built young colored man,” whose “movement” attracted the eyes of white on-lookers, turned out to be a woman in man's clothing. The article cites the woman living in a “shanty” dwelling with other Black brick workers. She is not named and is referred to using racist terms, thus halting the historical record in its tracks. [10]

A TIME OF TRANSITION

As women transitioned out of their households and into manufacturing and the brickyards, women began to take on the traditional roles of men.

Having managed the household accounts, women became proficient at taking on more roles dealing with money, such as managing the company accounts, managing capital, land leasing, collecting tenants’ rents, and other businesses related to brickmaking.

Ledgers in the Museum’s archives of James W. Gillies, a prominent Haverstraw and Hackensack brick manufacturer, help illuminate this growing trend of women gaining status by obtaining small amounts of capital, a status called “petty bourgeois,” as well as larger amounts of capital or land deeds, a status called “bourgeois.”

In the museum archives, there is a clear story of the transition from one status to another. One ledger book was reserved primarily for land leases and gives a great deal of insight into women’s dealings and ownership within the brick industry

REMARKABLE WOMEN

Casscles’ Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

One of the women listed in Gillies’ ledger was Johanna Morrissey, cited for purchasing a lease of land from James. [11]

Newspapers help corroborate her influence. In 1887, Mrs. Morrissey was one of the first stockholders in the Haverstraw People’s Bank. In 1893, Johanna donated window no. 6 to St. Peter’s Church, which is still there today. When she passed away in 1911, she was described by the Rockland County Times as “successful and scrupulously honest,” being invested not only in groceries and other businesses but “brickmaking enterprises and brick transporting boats.” [12]

Another one of these women listed was Catherine A. Hedges. Catherine purchased a lease of land from 1880-1881. Hedges also obtained bourgeois status and owned land. In May of 1880, the Rockland County Messenger reported her selling land to John W. Gillies for $900. [13] In 1886, the Rockland County Messenger published a mortgage sale, the description of which bordered the land of Catherine. [14]

Another two women that leased land included “Caroline L. G. Scott” and “Mrs. Oldfield, the latter woman being an example of the repercussions of coverture. Due to married women still being considered as men’s property to various extents, married women had their maiden names stripped from them in favor of their husbands, and were often addressed with their husband’s surnames.

Despite having her first name erased to a great extent, Mrs. Oldfield was most certainly a prominent brick producer, with Gillies’ ledger citing the workers on her leased yard producing an “excess of brick made” at “3,150,000” for the year 1887. [15]

Another unnamed woman is “Mrs. M. A Gillies.” While her familial relationship with James is unknown, the latter’s ledgers still illuminate Margaret’s dealings in the brick business. Although James initially received all of the earnings of his brick business into his Hackensack Bank Account, multiple checks addressed to Margaret — the latter of which cite “Barge Earnings” — show that not only did she manage company barge boats but earned income for them as well. [16]

KING’S DAUGHTERS’ SOCIETY

Further research into the Haverstraw King’s Daughters’ Society (HKD) — a dues-paying organization composed of many wives of brickyard owners — found that the practices of coverture were especially prevalent amongst bourgeois men who were invested in the trade. Here, women are listed without any real identification of themselves, i.e., “Mrs. Frank L. Dunnigan,” “Mrs. Denton Fowler,” “Mrs. Frank DeNoyelles,” etc. [17]

It is also worth noting how many of these women’s class positions affected their labor outside of dealing with capital. Upper-class women saw fit to dedicate themselves to charity work. HKD was founded in 1891 as the “Haverstraw Ladies’ Home Mission Circle” and dedicated itself to charity work. Its first effort was a “sewing circle for the benefit of the village poor.” Mrs. M. A. Gillies was the organization’s second president and third vice president, and meetings were held in the family’s house on Second Street. [18]

However, as described in their Christmas relief, they only saw fit to dedicate charity to those perceived as “the worthy poor.”[19]

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM WOMEN IN HISTORY?

Despite a woman’s class status, all faced gender discrimination in Haverstraw and the brick industry. Yet, it can also be said that this discrimination expressed itself more prominently depending on the context.

Despite the numerous legal boxes they were forced into, upper-class women had the luxury of capital, allowing them to employ others, including other women. Meanwhile, working-class women who kept the accounts of the local stores contributed to their families’ incomes without being recognized. Many black, brown, and Asian women not only worked for wages but were often barred from many employment opportunities in favor of white men and women.

Finding the untold stories of women takes a great deal of research and detective work while cross-referencing sources. At the Haverstraw Brick Museum, we encourage our readers and visitors to share their stories by contributing to the history of the village and brick industry.

The accounts of women in your families and your research can help repair the historical record and SHINE A light ON THE TOO often neglected or UNTOLD stories.

Picnic at Emeline, De Noyelles Collection, ©Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

Written by Luke Spaltro, Museum Historian. Edited by Rachel Whitlow, Executive Director.

Citations

[1] Coverture dates back to Medieval times, and was later brought to what became the United States by Dutch, English, and other groups of settlers. “Women & The American Story: Coverture,” The New York Historical. https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/coverture/

[2] “Haverstraw Items,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XIV, No. 40, Jul. 11, 1903, 8. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19030711&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-41-byDA-txt-txIN-%22men+wanted%22------

[3] Numerous Black and Brown women throughout history have pointed towards this intersectionality, from abolitionist Sojourner Truth of the Hudson valley, to Claudia Jones who is attributed with coining the term.

[4] “Haverstraw Items,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XIV, No. 12, 8. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19021206.2.70.1&srpos=14&e=------190-en-20-rocklandctytimes-1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22silk+mill%22------

[5] “Great Bargains at SANDUSKY’s,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XV, No. 9, Dec. 5, 1903, 6. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19031205.2.37.4&srpos=1&e=-------en-20-rocklandctytimes-1--txt-txIN-%22Sandusky%27s%22+%22lunch+boxes%22------

[6] “Employers of Labor,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XII, No. 14, Dec. 22, 1900, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19001222.2.4&srpos=12&e=------190-en-20-rocklandctytimes-1--txt-txIN-women+work------

[7] “Brick Yard Men Wanted.,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 31, Apr. 21, 1900, 8. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000421.2.94.3&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------

[8] “Woman Working,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XI, No. 33, May 5, 1900, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19000505.2.3&srpos=5&e=------190-en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22darkies%22------

[9] Shankey Brick Co., Pocket Leather Ledger Book, Sep. 1894-Jan. 1894, De Noyelles Collection, Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

[10] “Woman Working,” 1.

[11] James W. Gillies, Lease Book, Jan. 1876-Dec. 1889, Casscles Collection, Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

[12] “Obituary,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXII, No. 48, Sep. 23, 1911, 5. “Placing Memorial Windows,” Rockland County Messenger, Vol. LI, No. 10, Jul. 9, 1893, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandmessenger18960709.2.37&srpos=3&e=-------en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22johanna+morrissey%22------

[13] “Deeds Recorded,” Rockland County Journal, Vol. XXX, May 22, 1880, 5. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctyjournal18800522.2.25.1&srpos=9&e=------188-en-20--1-byDA-txt-txIN-%22hedges%22------

[14] James W. Gillies, Hackensack Bank Check Book, 1881, Casscles Collection, Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives; “Mortgage Sale,” City & Country, No. 1437, Dec. 4, 1886, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=ifacfgic18861204-01.1.2&srpos=186&e=------188-en-20--181-byDA-txt-txIN-%22hedges%22------.

[15] Gillies, Lease Book.

[16] James W. Gillies, Hackensack Bank Check Book, Nov. 1889-Jul.1893, Casscles Collection, Haverstraw Brick Museum Archives.

[17] Report of the Work of the King’s Daughters’ Society,” Rockland County Times, Vol. XXIII, No. 5, Nov. 25, 1911, 2. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandctytimes19111125.1.2&srpos=22&e=------191-en-20--21-byDA-txt-txIN-%22dunnigan%22------

[18] “Building Fund Souvenir: THE KING’S DAUGHTER’S SOCIETY OF HAVERSTRAW N.Y. AND ITS PUBLIC LIBRARY” (Haverstraw: N.Y., 1900), 4-5. Library History “Souvenir Book” + Copy, 1.4.001.1900, KDPL.

[19] “Messenger’s Poor Fund,” Rockland County Messenger, Vol. XLVIII, No. 32, Dec. 7, 1893, 1. https://news.hrvh.org/veridian/?a=d&d=rocklandmessenger18931207.2.18&srpos=131&e=------189-en-20--121-byDA-txt-txIN-%22gillies%22------